Embarking on an Enormous Project

Jul 22, 2017

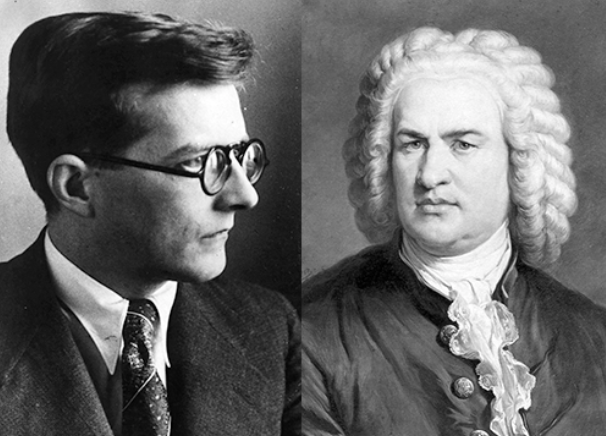

Somewhere during the Spring Semester 2017 at Peabody, I had a revelation. I was working with a student on Bartok’s Mikrokosmos, and somehow my student and I got into a conversation about counterpoint, during which I mused out loud, “How cool would it be to juxtapose ALL of Bach’s Preludes and Fugues with ALL of Shostakovich’s Preludes and Fugues?” My student agreed that it would, indeed, be super cool. And so an idea was born.

I wondered, “How many concerts would that take, to play all that music?”

The answer is 4.

I have always felt close to Bach. When I was growing up, at the encouragement of my teachers Julian Martin (1986-1987) and later Jeanne Kierman Fischer (1988-1992), I played one full recital per year, starting at age 13. I always began my programs with Bach. I had occasion recently to remember my very first solo recital when I came across its printed program in an old box of papers my father had saved and sent me. (Thanks, Dad.) I began my first full public concert with Bach’s Keyboard Concerto in F Minor. In later years, I started recitals with a French Suite, or a Partita, sometimes a Prelude and Fugue. But somehow, it was centering to me to begin my two hours on stage with some of the purest, most spiritual music in the piano repertoire.

Or should I say, more appropriately, the keyboard repertoire. That may be a blog for another day, how Bach had not even met the piano on which many of us now perform his works —– OR DID HE? There are rumors that he did discover and play on a Cristofori-designed fortepiano late in his life. More on that another time.

I recall one of my first lessons with Brian Connelly, the teacher who blew my mind regularly from my sophomore year at Rice University’s Shepherd School of Music through the end of my Masters Degree, 6 years in total. When I shared with Brian my habit of beginning all recitals with Bach, he promptly declared, “Well, we won’t be doing THAT anymore.” Brian loved Bach, but felt the need to broaden my horizons and make sure I didn’t become dependent on any one style.

One of the most remarkable and unique things about J.S. Bach’s keyboard music is that it is bereft of any extramusical indications. Bach must be the polar opposite of Bela Bartok in that regard, Bartok who OVERLY notated as a general rule. Almost every note in Bartok’s music has a dot, a dash, a hash mark, a slur, a dynamic, a crescendo, a verbal expressive cue. Bach could not be farther from this. In his keyboard music we see no tempo markings. We see no dynamics, no articulations, no indications of whether notes should be staccato, portato, legato, connected, detached. We see no indications of crescendo or diminuendo, whether a phrase or a sequence should be rising or falling in volume and energy level. Bach’s music is a clean slate. It is mathematical and perfect in its construction and achieves a sublime state that transcends the need for extraneous detail. This is why performances of Bach are so personal, so different from one artist to the next. Musicians are given so much latitude to make their own decisions that interpretations naturally vary immensely. Bach’s music survives this and emerges from any interpretation unassaulted and unblemished – because the nature of his compositional style is so scientific, so precise, so regimented, so controlled – and through those qualities so celestial, so metaphysical – that its power transcends the interpretation of any one performer. The message is potent. It will not and cannot be lost.

The music of Bach is the purest, most adaptable (it can be played on any keyboard instrument with equal success), most rigorously intellectual and yet flexible writing of any I can think of. As a matter of fact, it can only be rivaled by the work of one other composer… you guessed it, Shostakovich.

Shostakovich, too, leaves much to the performer. Few dynamic indications, few articulative indications, and few tempo indications (though it must be said, more than from Johann Sebastian.) Shostakovich’s music, like Bach’s, finds a potency through complexity masked as simplicity. Both of these composers rely almost entirely on counterpoint to carry the weight of their message. I leave it to a future blog posting to tackle the challenge of unpacking for you what counterpoint is, and why it is such a powerful vehicle.

Presenting these two composers on the same series of programs is both shockingly unorthodox and the most natural partnership one could imagine.

I look forward to sharing this journey with you, my friends, family, and interested parties. Some of these 8 hours of music I have played before, but the majority of it I have not. I expect some confirmations of things I have already known about these two composers and their relationship to each other. And I also fully expect to be astounded than a few times as I discover the intricacies of what Bach and Shostakovich have in common. I’m excited for you to join me in my exploration.